ਜੀ. ਸੰਪਥ

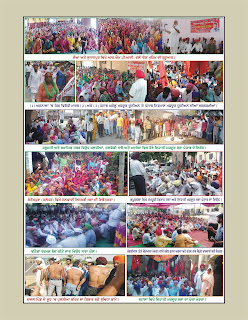

16 ਸਤੰਬਰ 2016 ਨੂੰ ਜੰਤਰ ਮੰਤਰ, ਨੇੜੇ ਪਾਰਲੀਮੈਂਟ ਸਟਰੀਟ, ਨਵੀਂ ਦਿੱਲੀ ਵਿਖੇ ਇਕ ਅਜਿਹੀ ਦਲਿਤ ਰੈਲੀ ਦਾ ਆਯੋਜਨ ਹੋਇਆ ਜੋ ਭੂਤਕਾਲ ਵਿਚ ਵਾਪਰੀਆਂ ਅਜਿਹੀਆਂ ਘਟਨਾਵਾਂ ਨਾਲੋਂ ਇਕ ਖਾਸ ਪੱਖ ਤੋਂ ਨਿਵੇਕਲੀ ਸੀ। ਵੱਖਰੇਵਾਂ ਇਸ ਗੱਲੋਂ ਸੀ ਕਿ ਇਸ ਰੈਲੀ ਵਿਚ ਪ੍ਰਕਾਸ਼ ਅੰਬੇਦਕਰ, ਰਾਧਿਕਾ ਵੇਮੁੱਲਾ ਅਤੇ ਜਿਗਨੇਸ਼ ਮੇਵਾਨੀ ਦੇ ਮੌਢੇ ਨਾਲ ਮੋਢਾ ਜੋੜਕੇ ਵੱਡੀ ਗਿਣਤੀ ਵਿਚ ਸੀਤਾ ਰਾਮ ਯੈਚੁਰੀ, ਸੁਧਾਕਰ ਰੈਡੀ ਅਤੇ ਡੀ. ਰਾਜਾ ਵਰਗੇ ਖੱਬੇ ਪੱਖੀ ਨੇਤਾ ਵੀ ਬੁਲਾਰਿਆਂ 'ਚ ਸ਼ਾਮਲ ਸਨ। ਹੈਰਾਨੀ ਇਸ ਗੱਲ ਦੀ ਹੈ ਕਿ ਉਥੇ ਦਲਿਤ ਪਛਾਣ ਵਜੋਂ ਜਾਣੇ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਨਾਅਰੇ ''ਜੈ ਭੀਮ'' ਦੇ ਨਾਲ ਹੀ ਖੱਬੇ ਪੱਖੀ ਹਲਕਿਆਂ ਤੋਂ ਬਾਹਰ ਘੱਟ ਹੀ ਸੁਣੇ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਨਾਅਰੇ 'ਲਾਲ ਸਲਾਮ' ਵੀ ਲੱਗ ਰਹੇ ਸਨ।

ਜੇਕਰ 'ਜੈ ਭੀਮ' ਅਤੇ 'ਲਾਲ ਸਲਾਮ' ਦਾ ਅਜਿਹਾ ਗੱਠਜੋੜ ਸੱਚਮੁੱਚ ਕਿਸੇ ਰਾਜਨੀਤਕ ਪ੍ਰੋਗਰਾਮ ਵਿਚ ਤਬਦੀਲ ਹੋ ਜਾਂਦਾ ਹੈ ਤਾਂ ਇਹ ਖੱਬੇ ਪੱਖੀ ਅਤੇ ਦਲਿਤ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਵਿਚ ਇਕ ਹਾਂ ਪੱਖੀ ਮਹੱਤਵਪੂਰਨ ਮੋੜਾ ਹੋਵੇਗਾ। ਊਨਾ, ਗੁਜਰਾਤ ਵਿਚ ਹੋਏ ਤਾਜਾ ਦਲਿਤ ਸੰਘਰਸ਼, ਸੰਭਾਵਨਾਵਾਂ ਦੀ ਕਿਰਨ ਦਿਖਾਉਂਦੇ ਹਨ ਜੋ ''ਜੈ ਭੀਮ'' ਅਤੇ 'ਲਾਲ ਸਲਾਮ' ਦੇ ਨਾਅਰਿਆਂ ਦੀ ਇਕਮਿਕਤਾ ਤੋਂ ਵੀ ਉਪਰ ਪੱਧਰ ਦੇ ਪ੍ਰੋਗਰਾਮਾਂ ਦੇ ਦੌਰ 'ਚ ਪਹੁੰਚ ਸਕਦੀਆਂ ਹਨ।

ਗੁਜਰਾਤ ਦੇ ਸਬਕ

ਊਨਾ ਵਿਖੇ ਅਖੌਤੀ ਗਊ ਰੱਖਿਅਕਾਂ ਹੱਥੋਂ ਮੱਧਯੁਗੀ ਜ਼ੁਲਮ ਦਾ ਸ਼ਿਕਾਰ ਹੋਏ ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਦੀ ਘਟਨਾ ਚੋਂ ਗੁਜਰਾਤ ਵਿਚ ਉਪਜਿਆ ਲੋਕ ਉਭਾਰ ਪਹਿਲਾਂ ਹੀ ਦੋ ਵੱਡੀਆਂ ਪ੍ਰਮੁੱਖ ਜਿੱਤਾਂ ਪ੍ਰਾਪਤ ਕਰ ਚੁੱਕਾ ਹੈ। ਪਹਿਲੀ ਜਿੱਤ ਇਹ ਕਿ ਇਸ ਉਭਾਰ ਨੇ ਸੂਬਾਈ ਰਾਜ ਪ੍ਰਬੰਧ ਨੂੰ ਇਸ ਗੱਲ ਲਈ ਮਜ਼ਬੂਰ ਕਰ ਦਿੱਤਾ ਹੈ ਕਿ ਉਸਨੇ ਅਹਿਮਦਾਬਾਦ ਜ਼ਿਲ੍ਹੇ ਦੀ ਢੋਲਕਾ ਬਲਾਕ ਵਿਚ ਸਰੋਦਾ ਪਿੰਡ ਦੇ 115 ਦਲਿਤ ਪਰਿਵਾਰਾਂ ਨੂੰ 220 ਵਿਘੇ ਸਰਕਾਰੀ ਜ਼ਮੀਨ ਦੀ ਵੰਡ ਦਾ ਤੌਰ ਤਰੀਕਾ ਸ਼ੁਰੂ ਕਰ ਦਿੱਤਾ ਹੈ।

ਦੂਜੀ ਜਿੱਤ ਅਹਿਮਦਾਬਾਦ ਮਿਊਂਸੀਪਲ ਕਾਰਪੋਰੇਸ਼ਨ ਦੇ ਸਫਾਈ ਕਰਮਚਾਰੀਆਂ ਦੀ ਹੋਈ ਹੈ ਜਿਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਨੇ ਕਿ 36 ਦਿਨ ਲੰਬੀ ਹੜਤਾਲ ਕੀਤੀ ਸੀ। ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਮੰਗਾਂ, ਜਿਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਵਿਚ ਠੇਕੇ ਤੇ ਰੱਖੇ ਵਰਕਰਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਰੈਗੂਲਰ ਕਰਨਾ, ਪ੍ਰਾਵੀਡੈਂਟ ਫੰਡ ਸਕੀਮ ਦੀ ਵਿਵਸਥਾ ਕਰਨਾ ਅਤੇ ਸਿਹਤ ਸਹੂਲਤਾਂ ਦੇਣਾ, ਘੱਟੋ ਘੱਟ ਉਜਰਤਾਂ ਦੀ ਗਰੰਟੀ ਕਰਨਾ, ਸਾਰੇ ਕਾਮਿਆਂ ਲਈ ਸੇਫਟੀ ਮਸ਼ੀਨਰੀ ਦਾ ਪ੍ਰਬੰਧ ਕਰਨਾ, ਐਕਸੀਡੈਂਟ ਦੌਰਾਨ ਹੋਈ ਮੌਤ ਦਾ ਅਤੇ ਹਾਦਸਿਆਂ ਦੌਰਾਨ ਲੱਗੀਆਂ ਸੱਟਾਂ ਲਈ ਵਰਕਰ ਦੇ ਰਿਸ਼ਤੇਦਾਰ ਨੂੰ ਨੌਕਰੀ ਤੇ ਢੁਕਵਾਂ ਮੁਆਵਜ਼ਾ ਦੇਣਾ ਅਤੇ 2011 ਤੋਂ ਪ੍ਰਾਵੀਡੈਂਟ ਫੰਡ ਦੇ ਸਾਰੇ ਬਕਾਇਆਂ ਦਾ ਭੁਗਤਾਨ ਕਰਨਾ ਆਦਿ ਸ਼ਾਮਲ ਸਨ ਅਤੇ ਇਹ ਸਾਰੀਆਂ ਹੀ ਮੰਗਾਂ ਪਦਾਰਥਕ ਸਨ। ਅਹਿਮਦਾਬਾਦ ਮਿਊਂਸਿਪਲ ਕਾਰਪੋਰੇਸ਼ਨ ਵਲੋਂ ਬਦਲੇ ਸਿਆਸੀ ਹਾਲਾਤ 'ਚ ਇਹ ਸਾਰੀਆਂ ਹੀ ਮੰਗਾਂ ਮੰਨੀਆਂ ਗਈਆਂ ਹਨ।

ਇਹ ਦੋ ਉਦਾਹਰਣਾਂ ਹਨ ਜਿਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਵਿਚ ਰਾਸ਼ਟਰੀਆ ਦਲਿਤ ਅਧਿਕਾਰ ਮੰਚ ਅਤੇ ਊਨਾ ਦਲਿਤ ਅਤਿਆਚਾਰ ਵਿਰੋਧੀ ਸੰਘਰਸ਼ ਸਮਿਤੀ ਵਲੋਂ ਜੋ ਆਪਣੀ ਪਛਾਣ ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਵਾਲੀ ਰੱਖਦੀਆਂ ਹਨ, ਦਲਿਤ ਗੁੱਸੇ ਨੂੰ ਇਕ ਵਿਹਾਰਕ ਰਾਜਨੀਤਿਕ ਪ੍ਰੋਜੈਕਟ ਵਜੋਂ ਸਥਾਪਿਤ ਕੀਤਾ ਗਿਆ। ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਜਥੇਬੰਦੀਆਂ ਦੇ ਨਾਲ ਹੀ ਇਸ ਕਾਰਜ ਵਿਚ ਗੁਜਰਾਤ ਫੈਡਰੇਸ਼ਨ ਆਫ ਟਰੇਡ ਯੂਨੀਅਨਜ਼, ਗੁਜਰਾਤ ਮਜ਼ਦੂਰ ਸਭਾ ਅਤੇ ਗੁਜਰਾਤ ਸੰਘਰਸ਼ ਮੰਚ ਵਰਗੀਆਂ ਸੰਗਰਾਮੀ ਅਤੇ ਨਾਲ ਹੀ ਸ਼ਹਿਰੀ ਹੱਕਾਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਜਥੇਬੰਦੀਆਂ ਨੇ ਵੀ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਨਾਲ ਮੋਢੇ ਨਾਲ ਮੋਢਾ ਜੋੜ ਕੇ ਕੰਮ ਕਰਨ ਲਈ ਹੀਲਾ ਕੀਤਾ। ਹਾਲਾਂਕਿ ਇਸ ਸਾਰੀ ਲਾਮਬੰਦੀ ਦੇ ਫਲ ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਹੀ ਮਿਲੇ ਪਰ ਮੰਗ ਪੱਤਰ ਦਾ ਸਾਰਾ ਚੌਖਟਾ ਪਛਾਣ ਅਧਾਰਤ ਨਾ ਹੋ ਕੇ ਪਦਾਰਥਕ ਮੰਗਾਂ ਵਾਲਾ ਹੀ ਰੱਖਿਆ ਗਿਆ। ਭੂਮੀ ਦੀ ਮਾਲਕੀ ਅਤੇ ਸਮਾਜਿਕ ਲਾਭਾਂ ਸਮੇਤ ਪੱਕੀ ਨੌਕਰੀ ਦੀ ਮੰਗ, ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਦੀ ਪਦਾਰਥਕ ਹੋਂਦ ਅਤੇ ਸਮਾਨ ਰੁਤਬੇ ਦੇ ਮਾਮਲੇ ਵਿਚ ਵੱਡੇ ਮਾਇਨੇ ਰੱਖਦੀ ਹੈ। ਪ੍ਰੰਤੂ ਦਲਿਤ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਦਾ ਪਦਾਰਥਕ ਮੰਗਾਂ ਨੂੂੰ ਉਭਾਰਨ ਦਾ ਲੱਛਣ ਪਹਿਲਾਂ ਕਦੀ ਨਹੀਂ ਰਿਹਾ।

ਇਹੀ ਘਾਟ ਖੱਬੇ ਪੱਖੀ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਵਿਚ ਉਲਟੇ ਤੌਰ 'ਤੇ ਦੇਖੀ ਗਈ ਹੈ ਜਿਸ ਨੇ ਕਦੇ ਵੀ ਗੰਭੀਰ ਤੌਰ ਤੇ ਜਾਤਪਾਤ ਦੇ ਮੁੱਦੇ ਨੂੰ ਨਹੀਂ ਲਿਆ ਅਤੇ ਨਾ ਹੀ ਦਲਿਤਾਂ 'ਤੇ ਹੁੰਦੇ ਅਤਿਆਚਾਰਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਅਤੇ ਨਾ ਹੀ ਆਮ ਜਾਤਪਾਤ ਖਿਲਾਫ ਆਪਣੀ ਜੁਝਾਰੂ ਪਛਾਣ ਅਨੁਸਾਰ ਲਾਮਬੰਦੀਆਂ ਕੀਤੀਆਂ। ਇਸ ਨੇ ਜਮਾਤੀ ਲੁੱਟ ਦੇ ਅਧੀਨ ਹੋ ਰਹੀ ਜਾਤੀ ਅਧਾਰਤ ਲੁੱਟ ਨੂੰ ਚੈਲੰਜ ਕਰੇ ਬਿਨਾਂ ਹੀ ਆਪਣੇ ਆਪ ਨੂੰ ਜਮਾਤੀ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਤੱਕ ਹੀ ਸੀਮਿਤ ਰੱਖਿਆ ਹੈ। ਇਸਦਾ ਵੱਡਾ ਕਾਰਨ ਜਾਤੀ ਅਧਾਰਤ ਮੁੱਦਿਆਂ 'ਤੇ ਮਜ਼ਦੂਰ ਜਮਾਤ ਦੇ ਵੰਡੇ ਜਾਣ ਦਾ ਡਰ ਸੀ। ਪ੍ਰੰਤੂ ਭਾਰਤੀ ਮਜ਼ਦੂਰ ਜਮਾਤ ਤਾਂ ਪਹਿਲਾਂ ਹੀ ਅਲੱਗ ਅਲੱਗ ਪਛਾਣਾਂ 'ਚ ਉਹ ਵੀ ਜਿਆਦਾਤਰ ਜਾਤ-ਅਧਾਰਤ ਪਛਾਣਾਂ ਵਿਚ ਵੰਡੀ ਪਈ ਸੀ। ਪੈਸੇ ਪੱਖੀਆਂ ਦੀ ਭਾਰਤੀ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਵਿਚ ਗੁੱਠੇ ਲਾਈਨ ਲੱਗਣ ਵਿਚ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਵਲੋਂ ਜਾਤ ਅਧਾਰਤ ਵੰਡ ਨੂੰ ਰੋਕ ਨਾ ਸਕਣਾ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੀ ਅਸਫਲਤਾ ਦਾ ਇਕ ਕਾਰਨ ਹੈ। ਅੰਬੇਦਰਵਾਦੀ ਆਲੋਚਕ ਜਾਤ ਅਧਾਰਤ ਲੁੱਟ ਤੇ ਖੱਬੀ ਲੀਡਰਸ਼ਿਪ ਵਿਚ ਉਪਰਲੀਆਂ ਜਾਤਾਂ ਦੇ ਭਾਰੂ ਰਹਿਣ ਨੂੰ ਦੋਸ਼ ਦਿੰਦੇ ਹਨ। ਸਚਮੁੱਚ ਹੀ ਖੱਬਿਆਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਪੋਲਿਟ ਬਿਊਰੋ 'ਤੇ ਕੇਂਦਰੀ ਕਮੇਟੀਆਂ ਵਿਚ ਬਹੁਤ ਹੀ ਘੱਟ ਦਲਿਤ ਹਨ।

ਬਿਲਕੁਲ ਇਸੇ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਹੀ ਅੰਬੇਦਰਵਾਦੀਆਂ ਦੀ ਖੱਬੇ ਪੱਖੀਆਂ ਦੁਆਰਾ ਕੀਤੀ ਜਾਂਦੀ ਆਲੋਚਨਾ ਵੀ ਨਿਰਆਧਾਰ ਨਹੀਂ। ਇਸਦਾ ਬਹੁਤ ਹੀ ਖੂਬਸੂਰਤ ਵਿਸ਼ਲੇਸ਼ਣ 'ਅਨੁਰਾਧਾ ਘਾਂਡੀ' ਵਲੋਂ ਆਪਣੇ ਲੇਖ 'ਜਾਤਪਾਤ ਦਾ ਸਵਾਲ' ਵਿਚ ਕੀਤਾ ਗਿਆ ਹੈ। ਇਸ ਲੇਖ ਵਿਚ ਉਹ ਲਿਖਦੀ ਹੈ ਕਿ ''ਰਾਜ ਕਰਦੀਆਂ ਜਮਾਤਾਂ ਨੇ ਸੁਚੇਤ ਰੂਪ ਵਿਚ ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਵਿਚ ਕੁੱਝ ਚੇਤਨ (ਖਾਂਦੇ ਪੀਂਦੇ) ਲੋਭਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਸਪਾਂਸਰ ਕੀਤਾ ਹੈ ਜਿਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਨੇ ਜਾਣਬੁੱਝ ਕੇ ਦਲਿਤ ਏਕਤਾ ਅਤੇ ਤੰਗ ਨਜ਼ਰ ਪਹੁੰਚ ਦੀ ਸਿਰਫ ਅਪੀਲ ਹੀ ਨਹੀਂ ਕੀਤੀ ਸਗੋਂ ਦੂਜੇ ਲੁੱਟੇ ਜਾਂਦੇ ਤਬਕਿਆਂ ਅਤੇ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਨੁਮਾਇੰਦਾ ਪਾਰਟੀਆਂ ਨਾਲ ਕਿਸੇ ਵੀ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੀ ਏਕਤਾ ਤੋਂ ਇਨਕਾਰੀ ਹੁੰਦਿਆਂ ਇਹ ਏਕਤਾ ਨਾ ਉਸਰਣ ਦੇਣ ਦਾ ਪੂਰਾ-ਪੂਰਾ ਯਤਨ ਕੀਤਾ ਹੈ।

ਪਛਾਣਵਾਦ ਦੀਆਂ ਸੀਮਾਵਾਂ ਸ਼੍ਰੀਮਤੀ ਅਨੁਰਾਧਾ ਘਾਂਡੀ ਦਾ ਮੂਲ ਮੁੱਦਾ ਇਹ ਹੈ ਕਿ ਦਲਿਤ ਅਤੇ ਪਛੜਿਆਂ ਦੀ ਜਾਤੀ ਅਧਾਰਤ ਏਕਤਾ ਲੰਬਾ ਸਮਾਂ ਅਮਲੀ ਤੌਰ 'ਤੇ ਨਹੀਂ ਚੱਲ ਸਕਦੀ ਕਿਉਂਕਿ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਆਪਸੀ ਜਮਾਤੀ ਵਿਰੋਧਤਾਈਆਂ ਹਨ। ਇਸ ਤੱਥ ਦੀ ਹੁਣੇ ਵਾਪਰੀਆਂ ਘਟਨਾਵਾਂ ਨੇ ਪੁਸ਼ਟੀ ਕੀਤੀ ਹੈ। ਦੇਸ਼ ਦੇ ਵੱਖ ਵੱਖ ਭਾਗਾਂ ਵਿਚ ਖੇਤੀਬਾੜੀ 'ਚ ਭਾਰੂ ਜਾਤਾਂ ਨੇ ਲਾਮਬੰਦੀ ਸ਼ੁਰੂ ਕੀਤੀ ਹੈ ਇਹ ਲਾਮਬੰਦੀ ਉਪਰਲੀਆਂ ਜਾਤਾਂ ਜੋ ਕਿ ਜ਼ਮੀਨ ਜਾਂ ਸਰਮਾਏ ਦੀਆਂ ਮਾਲਕ ਹਨ ਵਿਰੁੱਧ ਨਹੀਂ, ਬਲਕਿ ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਵਿਰੁੱਧ ਹੋਈ ਹੈ। ਰਾਜਸਥਾਨ ਵਿਚ ਗੁੱਜਰਾਂ ਤੋਂ ਬਾਅਦ ਹੁਣ ਹਰਿਆਣੇ ਦੇ ਜਾਟ, ਗੁਜਰਾਤ ਦੇ ਪਟੇਲ ਅਤੇ ਮਹਾਰਾਸ਼ਟਰ ਦੇ ਮਰਾਠੇ ਰਾਖਵੇਂਕਰਨ ਦੀ ਮੰਗ 'ਤੇ ਸੜਕਾਂ 'ਤੇ ਉਤਰੇ ਹਨ। ਇਸਦੇ ਨਾਲ ਹੀ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਨੇ ਅਨੁਸੂਚਿਤ ਜਾਤੀਆਂ ਤੇ ਕਬੀਲਿਆਂ (ਜ਼ੁਲਮ ਰੋਕੂ) ਕਾਨੂੰਨ ਦੀਆਂ ਧਾਰਾਵਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਨਰਮ ਕਰਨ ਦੀ ਮੰਗ ਵੀ ਕੀਤੀ ਹੈ। ਇਹ ਕੋਈ ਹੈਰਾਨੀਜਨਕ ਨਹੀਂ ਕਿ ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਦੇ ਕੁੱਝ ਹਿੱਸਿਆਂ ਵਿਚ ਇਹ ਅਹਿਸਾਸ ਖਾਸ ਤੌਰ 'ਤੇ ਗੁਜਰਾਤ ਵਿਚ ਜਿੱਥੇ ਉਹ ਸਿਰਫ 7% ਦੀ ਬਹੁਤ ਹੀ ਨਿਗੂਣੀ ਘੱਟ ਗਿਣਤੀ ਵਿਚ ਹਨ, ਪਨਪਿਆ ਹੈ ਕਿ ਪਛਾਣ ਅਧਾਰਤ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਨਾਲ ਉਹ ਸਿਰਫ ਇੱਥੋਂ ਤੱਕ ਹੀ ਪਹੁੰਚ ਸਕਦੇ ਸੀ। ਇਹ ਅਹਿਸਾਸ ਭਾਰਤੀ ਰਾਜਨੀਤਕ ਯਥਾਰਥ ਦੀਆਂ ਤਿੰਨ ਦੁਖਦਾਈ ਸਚਾਈਆਂ ਨਾਲ ਦੋ-ਚਾਰ ਹੋਣ ਦਾ ਹੈ।

ਪਹਿਲੀ, ਭਾਰਤੀ ਚੋਣ ਪ੍ਰਣਾਲੀ ਵਿਚ ਪਛਾਣ ਅਧਾਰਤ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਸਿਰਫ ਦਲਿਤ ਵੋਟ ਦੇ ਦਲਾਲਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਹੀ ਜਨਮ ਦੇ ਸਕਦੀ ਹੈ, ਜੋ ਕਿ ਵੱਧ ਤੋਂ ਵੱਧ ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਲਈ ਮਾਮੂਲੀ ਰਿਆਇਤਾਂ ਲੈ ਕੇ ਦੇ ਸਕਦੇ ਹਨ ਅਤੇ ਉਹ ਵੀ ਜਾਤ ਅਧਾਰਤ ਪ੍ਰਬੰਧ ਨੂੰ ਬਿਨਾਂ ਚੈਲਿੰਜ ਕੀਤੇ। ਜਾਂ ਫਿਰ ਇਹ ਜਾਤੀ ਅਹੁਦਾ ਪ੍ਰਾਪਤੀ ਨੂੰ ਸਮੁੱਚੀ ਬਰਾਦਰੀ ਲਈ ਅਖੌਤੀ ਸ਼ਕਤੀਕਰਨ ਦਾ ਨਾਂਅ ਦੇ ਸਕਦੇ ਹਨ। ਰਾਮਦਾਸ ਅਠਾਵਲੇ ਅਤੇ ਉਦਿਤ ਰਾਜ ਵਰਗੇ ਆਗੂਆਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਉਦਾਹਰਣਾ ਇਸ ਮੌਕਾਪ੍ਰਸਤ ਵਰਤਾਰੇ ਨੂੰ ਦਰਸਾਉਂਦੀਆਂ ਹਨ। ਜਿੱਥੋਂ ਤੱਕ ਮਾਇਆਵਤੀ ਦੀ ਬਹੁਜਨ ਸਮਾਜ ਪਾਰਟੀ ਦਾ ਸੰਬੰਧ ਹੈ, ਇਸ ਦੀ ਸਮਰੱਥਾ ਇਕ ਵਿਅਕਤੀ ਦੇ ਹੱਥਾਂ ਵਿਚ ਕੇਂਦਰਿਤ ਹੋਣ ਕਰਕੇ ਰੁਕ ਗਈ ਹੈ। ਉਹੀ ਬਿਮਾਰੀ ਜੋ ਕਿ ਭਾਰਤ ਦੀਆਂ ਬਾਕੀ ਰਾਜਨੀਤਕ ਪਾਰਟੀਆਂ ਵਿਚ ਪਹਿਲਾਂ ਹੀ ਹੈ।

ਦੂਜੀ, ਦਲਿਤ-ਪਛੜਿਆਂ ਦੀ ਏਕਤਾ ਹੈ ਜੋ ਕਿਸੇ ਤਬਦੀਲੀ ਲਈ ਲੋੜੀਂਦੀ ਘੱਟੋ ਘੱਟ ਤਾਕਤ ਲਈ ਜ਼ਰੂਰੀ ਲੋੜ ਹੈ। ਅੰਦਰੂਨੀ ਜਮਾਤੀ ਵਿਰੋਧਤਾਈਆਂ ਕਾਰਨ ਅਜੇ ਇਸ ਏਕਤਾ ਦੀ ਸ਼ੁਰੂਆਤ ਵੀ ਨਹੀਂ ਹੋਈ ਹੈ। ਦਲਿਤਾਂ 'ਤੇ ਜ਼ੁਲਮਾਂ ਦੇ ਦੋਸ਼ੀਆਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਜਾਤਾਂ 'ਤੇ ਇਕ ਝਾਤ ਮਾਤਰ ਹੀ ਇਸ ਸਾਰੇ ਵਿਚਾਰ ਨੂੂੰ ਰੱਦ ਕਰ ਦਿੰਦੀ ਹੈ। ਤੀਜੀ ਤੇ ਆਖਰੀ ਸੱਚਾਈ-ਪਬਲਿਕ ਸੈਕਟਰ ਵਿਨਿਵੇਸ਼ ਅਤੇ ਨਿੱਜੀਕਰਨ ਦੀ ਸਰਕਾਰੀ ਨੀਤੀ ਹੋਣ ਕਰਕੇ, ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਦੀ ਵੱਡੀ ਬਹੁਗਿਣਤੀ ਲਈ ਰਾਖਵਾਂਕਰਨ ਲੰਬੇ ਸਮੇਂ ਲਈ ਕੋਈ ਮੁੱਦਾ ਨਹੀਂ ਬਣ ਸਕਦਾ। ਇਹ ਇਕ ਅਜਿਹੀ ਕੌੜੀ ਸੱਚਾਈ ਹੈ ਜਿਸਨੂੰ ਕਿ ਦੂਜੀਆਂ ਭਾਰੂ ਜਾਤਾਂ ਜੋ ਰਾਖਵੇਂਕਰਨ ਲਈ ਲੜਦੀਆਂ ਹਨ, ਸਮਝਣ ਤੋਂ ਅਸਮੱਰਥ ਹਨ। ਪ੍ਰੰਤੂ ਦੇਰ ਸਵੇਰ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਵੀ ਇਸ ਦੀ ਸਮਝ ਆ ਜਾਵੇਗੀ। ਜੇਕਰ ਅਸੀਂ ਰਾਖਵੇਂਕਰਨ ਤੋਂ ਪਰ੍ਹੇ ਹਟ ਕੇ ਸੋਚੀਏ ਤਾਂ ਫਿਰ ਪਛਾਣ-ਆਧਾਰਤ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਕੋਲ ਮਹਿਜ ਵਾਅਦਾ ਕਰਨ ਲਈ ਹੈ ਵੀ ਕੀ? ਪੂਰਾ ਕਰਨ ਦੀ ਤਾਂ ਗੱਲ ਹੀ ਛੱਡੋ। ਮਹਿਜ ਰਾਜਨੀਤਿਕ ਤਕਾਜ਼ਾ ਨਿਰਧਾਰਤ (ਨਿਰਦੇਸ਼ਤ) ਕਰਦਾ ਹੈ ਕਿ ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਆਪਣੀ ਪਛਾਣ ਅਧਾਰਤ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਤੋਂ ਪਰ੍ਹਾਂ, ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਭਾਈਵਾਲਾਂ ਵੱਲ ਦੇਖਣਾ ਪਵੇਗਾ ਜੋ ਕਿ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੇ ਸਮਾਜਿਕ, ਰਾਜਨੀਤਕ ਤੇ ਪਦਾਰਥਕ ਸਰੋਕਾਰਾਂ ਨਾਲ ਸਾਂਝ ਰੱਖਦੇ ਹਨ। ਕਿਉਂਕਿ ਉਹ ਆਪਣੇ ਆਸਰੇ ਉਹ ਗਿਣਤੀ ਨਹੀਂ ਰੱਖਦੇ, ਜਿਸਦੇ ਸਹਾਰੇ ਉਹ ਆਪਣੇ ਜਾਤਪਾਤ ਦੇ ਦਾਬੂਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਕਰਾਰਾ ਜਵਾਬ ਦੇ ਸਕਣ ਜਾਂ ਫਿਰ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੀ ਜਾਤ ਦੇ ਦਾਬੂਆਂ ਦੁਆਰਾ ਸੰਚਾਲਤ ਪਾਰਟੀਆਂ ਦਾ ਵੋਟ ਬੈਂਕ ਬਣਨ ਤੋਂ ਬਚ ਸਕਣ। ਤਾਜੀ ਉਦਾਰਹਰਣ ਲਈਏ 'ਗਊ ਭਗਤਾਂ' ਵਲੋਂ ਕੀਤੀ ਹਿੰਸਾ ਦਾ ਨਿਸ਼ਾਨਾ ਮੁਸਲਮਾਨ ਅਤੇ ਦਲਿਤ ਦੋਵੇਂ ਸਨ ਜਿਸਦੇ ਸਿੱਟੇ ਵਜੋਂ ਦਲਿਤ ਮੁਸਲਿਮ ਏਕਤਾ ਦੀਆਂ ਹਮਾਇਤੀ ਆਵਾਜ਼ਾਂ ਵੀ ਉਠੀਆਂ ਪਰ ਕਿਉਂਕਿ ਮੁਸਲਮਾਨ ਇਕ ਘੱਟ ਗਿਣਤੀ ਦੀ ਪਛਾਣ ਵੀ ਰੱਖਦੇ ਹਨ ਇਸ ਲਈ ਅਜਿਹਾ ਦਲਿਤ-ਮੁਸਲਿਮ ਗਠਜੋੜ ਨਾ ਸਿਰਫ ਜਮਾਤੀ, ਸਗੋਂ ਜਾਤੀ ਵਿਰੋਧਤਾਈਆਂ ਨਾਲ ਵੀ ਭਰਪੂਰ ਹੈ ਅਤੇ ਇਸ ਨੂੰ ਸੌਖਿਆਂ ਹੀ ਤੋੜਿਆ ਜਾ ਸਕਦਾ ਹੈ ਜਿਵੇਂ ਕਿ ਉਤਰ ਪ੍ਰਦੇਸ਼ ਵਿਚ ਅਜਿਹੇ ਦਲਿਤ-ਮੁਸਲਿਮ ਏਕਤਾ ਕਰਾਉਣ ਦੇ ਸਾਰੇ ਯਤਨ ਫੇਲ੍ਹ ਹੋਏ ਹਨ।

ਦਲਿਤ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਦੇ ਪ੍ਰਬੰਧਕਾਂ ਕੋਲ ਆਪਣੀ ਹੀ ਜਾਤ ਦੇ ਉਪਰਲੇ ਤਬਕਿਆਂ ਅਤੇ ਜਾਤੀ ਦਾਬੂਆਂ ਵਿਚਾਲੇ ਹੁੰਦੀ ਜਮਾਤੀ ਭਿਆਲੀ ਦਾ ਕੋਈ ਜਵਾਬ ਨਹੀਂ ਅਤੇ ਨਾ ਹੀ ਇਸ ਗੱਲ ਦਾ ਜਵਾਬ ਹੈ ਕਿ ਜਾਤੀ ਦਾਬੂਆਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਗਰੀਬ ਅਤੇ ਅਮੀਰ ਜਮਾਤਾਂ ਵਿਚ ਜਾਤੀ ਸਾਂਝ ਕਿਵੇਂ ਹੈ? ਇਹ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਓਨਾ ਚਿਰ ਅੱਗੇ ਨਹੀਂ ਵੱਧ ਸਕਦੀ ਜਿੰਨਾ ਚਿਰ ਇਹ ਸਾਰੇ ਸਾਧਣਹੀਣ ਲੋਕਾਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਪਦਾਰਥ ਉਮੰਗਾਂ ਦੀ ਦੁਖਦੀ ਰਗ 'ਤੇ ਹੱਥ ਨਹੀਂ ਰੱਖਦੀ। ਇਹ ਸਾਧਣਹੀਨ ਲੋਕ ਨਾ ਸਿਰਫ ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਵਿਚੋਂ ਹੀ ਹਨ ਸਗੋਂ ਦੂਜੀਆਂ ਪਛੜੀਆਂ ਸ੍ਰੇਣੀਆਂ ਅਤੇ ਉਪਰਲੀਆਂ ਜਾਤਾਂ ਵਿਚੋਂ ਵੀ ਹਨ। ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਵਿਚ ਬੇਜਮੀਨੇ ਲੋਕ, ਠੇਕਾ ਮਜ਼ਦੂਰ, ਕਰਜਈ ਕਿਸਾਨ ਅਤੇ ਪ੍ਰਵਾਸੀ ਵਰਕਰ ਸ਼ਾਮਲ ਹਨ।

ਇਸੇ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਨਾਲ ਹੀ ਖੱਬੀ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਦਾ ਓਨਾ ਚਿਰ ਕੋਈ ਭਵਿੱਖ ਨਹੀਂ ਜਿੰਨਾ ਚਿਰ ਇਹ ਸਮਾਜਿਕ ਤੌਰ 'ਤੇ ਦੱਬੇ ਕੁਚਲੇ ਲੋਕਾਂ ਦੀਆਂ ਜਮਹੂਰੀ ਉਮੰਗਾਂ ਦੀ ਤਰਜਮਾਨੀ ਨਹੀਂ ਕਰਦੀ ਅਤੇ ਇਹ ਪਛਾਣ ਨਹੀਂ ਕਰਦੀ ਕਿ ਜਾਤਪਾਤ ਦਾ ਖਾਤਮਾ ਹੀ ਉਹ ਸਿਫਤ ਹੈ ਜੋ ਅੱਗੋਂ ਕਿਸੇ ਅਗਾਂਹਵਧੂ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਦੀ ਸੰਭਾਵਨਾ ਨੂੰ ਜਨਮ ਦਿੰਦੀ ਹੈ। ਅਰਧ-ਜਗੀਰੂ, ਅੱਧ ਮਾਡਰਨ ਮੁਲਕ ਭਾਰਤ ਵਿਚ ਜਾਤਪਾਤ ਵਿਰੋਧੀ ਹੋਣ ਤੋਂ ਬਿਨਾਂ ਇਕੱਲੇ ਸਰਮਾਏਦਾਰੀ ਵਿਰੋਧੀ ਲਹਿਰ ਦੀ ਕੋਈ ਯੁਗ ਪਲਟਾਊ ਸਮਰੱਥਾ ਨਹੀਂ ਹੈ। ਅਜਿਹੀ ਸਮਝਦਾਰੀ ਖੱਬੀ ਧਿਰ ਨੂੰ ਅਜੋਕੇ ਦੌਰ ਵਿਚ ਦਲਿਤ ਤਾਕਤਾਂ ਨਾਲ ਹੱਥ ਮਿਲਾਉਣ ਦੇ ਯੋਗ ਬਨਾਉਂਦੀ ਹੈ। ਤਾਂ ਕਿ ਉਹ ਆਪਣਾ ਹਮਲਾ ਜਿੰਨੀ ਊਰਜਾ ਨਾਲ ਸਾਮਰਾਜਵਾਦ ਨੂੰ ਭੰਡਣ 'ਤੇ ਲਾਉਂਦੇ ਹਨ ਓਨਾ ਹੀ ਤਿੱਖਾ ਹਮਲਾ ਜਾਤਪਾਤ 'ਤੇ ਵੀ ਕਰ ਸਕਣ।

ਹਿੱਤਾਂ ਦੀ ਕੁਦਰਤੀ ਖਿੱਚ ਬਿਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਸ਼ੱਕ, ਖੱਬੀ ਅਤੇ ਦਲਿਤ ਰਾਜਨੀਤੀ ਦਾ ਮਿਲਾਨ ਕੋਈ ਨਵੀਂ ਘਟਨਾ ਵੀ ਨਹੀਂ। 'ਮਾਰਕਸ' ਅਤੇ ਅੰਬੇਦਕਰ' ਪਹਿਲਾਂ ਵੀ ਇਕੱਠੇ ਰਹਿ ਚੁੱਕੇ ਹਨ। ਖਾਸ ਤੌਰ ਤੇ 1950ਵਿਆਂ ਵਿਚ ਜਦੋਂ ਅੰਬੇਡਕਰ ਨੇ ਭਾਰਤੀ ਕਮਿਊਨਿਸਟ ਪਾਰਟੀ ਨਾਲ ਮਿਲ ਕੇ ਭੂਮੀਹੀਣ ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਸਰਕਾਰੀ ਜ਼ਮੀਨਾਂ ਵੰਡ ਕੇ ਦੇਣ ਦੇ ਸੰਘਰਸ਼ਾਂ ਦੀ ਅਗਵਾਈ ਕੀਤੀ ਸੀ। ਫਿਰ ਦੁਬਾਰਾ 1970ਵਿਆਂ ਵਿਚ ਮਹਾਰਾਸ਼ਟਰ ਵਿਚ ਦਲਿਤ ਪੈਂਥਰ ਲਹਿਰ ਚੱਲੀ, ਸਰਕਾਰੀ ਤਸ਼ੱਦਦ, ਉਪਰਲੀਆਂ ਜਾਤਾਂ ਦੀ ਹਿੰਸਾ (ਸ਼ਿਵ ਸੈਨਾ ਦੀ ਅਗਵਾਈ 'ਚ) ਅਤੇ ਇਨਾਮਾਂ ਅਤੇ ਚੋਣ ਟਿਕਟਾਂ ਦੇ ਲਾਲਚਾਂ ਰਾਹੀਂ ਫੁਟ ਪਾਉਣ ਸਮੇਤ ਸਾਰੇ ਕੁੱਝ ਨੂੰ ਰਲਾ ਮਿਲਾ ਕੇ ਇਸ ਖਾੜਕੂ ਖੱਬੇ ਪੱਖੀ ਦਲਿਤ ਉਭਾਰ ਨੂੰ ਰੋਕਿਆ ਜਾ ਸਕਿਆ ਸੀ।

ਅੱਜ ਸਰਮਾਏ ਉਤੇ ਕਾਬਜ ਕੁਝ ਜਾਤਪਾਤ ਦੀਆਂ ਤਾਕਤਾਂ ਅਤੇ ਸਰਕਾਰੀ ਮਸ਼ੀਨਰੀ ਦਾ ਗੱਠਜੋੜ ਇਕ ਪਾਸੇ ਅਤੇ ਸਮਾਜਿਕ ਤੌਰ 'ਤੇ ਦੱਬੇ ਕੁਚਲੇ ਲੋਕਾਂ ਦਾ ਜਨ ਸਮੂਹ ਅਤੇ ਆਰਥਿਕ ਤੌਰ 'ਤੇ ਗੁੱਠੇ ਲਾਈਨ ਲਾਏ ਲੋਕ ਦੂਜੇ ਪਾਸੇ ਖੜੋਤੇ ਹਨ। ਰਾਜ ਕਰਦੀ ਜਮਾਤ ਸਦਾ ਦੀ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਜਾਤਪਾਤ ਦੀਆਂ ਵੰਡੀਆਂ ਤੋਂ ਪਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਆਪਣੇ ਜਮਾਤੀ ਹਿੱਤਾਂ ਬਾਰੇ ਪੂਰੀ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਸੁਚੇਤ ਹੈ। ਪ੍ਰੰਤੂ ਮਜ਼ਦੂਰ ਜਮਾਤ, ਖਾਸ ਤੌਰ 'ਤੇ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਵਿਚੋਂ ਦਲਿਤ ਅਤੇ ਦੂਜੀਆਂ ਪਛੜੀਆਂ ਸ਼੍ਰੇਣੀਆਂ ਆਪਣੀ ਬੇਸ਼ੁਮਾਰ ਪਛਾਣਾਂ 'ਚ ਵੰਡੀ ਪਈ ਹੈ। ਇਹ ਪਛਾਣਾਂ ਨੇ ਅਜਿਹੇ ਆਪਸੀ ਵਿਰੋਧ ਸਹੇੜੇ ਹਨ ਕਿ ਉਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੀ ਜਮਾਤੀ ਪਛਾਣ ਇਸ ਵਿਚ ਦੱਬੀ ਪਈ ਹੈ। ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਖੱਬੇ ਪੱਖੀਆਂ ਦੀ ਇਸ ਕਰਕੇ ਵੀ ਲੋੜ ਹੈ ਕਿ ਹੋਰ ਕੋਈ ਵੀ ਰਾਜਨੀਤਕ ਤਾਣਾਬਾਣਾ ਨਹੀਂ ਜੋ ਇਕ ਪ੍ਰੋਗਰਾਮ ਦੇ ਤੌਰ 'ਤੇ ਮਜ਼ਦੂਰ ਜਮਾਤ ਦੇ ਮੁੱਦੇ ਜਿਵੇਂ ਚੰਗੀਆਂ ਉਜਰਤਾਂ, ਰੁਜ਼ਗਾਰ ਸੁਰੱਖਿਆ, ਪੈਨਸ਼ਨ, ਠੇਕਾ ਮਜ਼ਦੂਰੀ ਦਾ ਖਾਤਮਾ ਵਰਗੀਆਂ ਨੂੰ ਚੁੱਕਦਾ ਹੋਵੇ। ਖੱਬੇ ਪੱਖੀਆਂ ਲਈ ਵੀ ਮਹਿਜ ਹੋਂਦ ਖਾਤਰ ਵੀ ਦਲਿਤ ਮੁੱਦੇ ਚੁੱਕੇ ਜਾਣੇ ਚਾਹੀਦੇ ਹਨ। ਇਹ ਸਮਝ ਲੈਣਾ ਚਾਹੀਦਾ ਹੈ ਕਿ ਮਜ਼ਦੂਰ ਜਮਾਤ ਦੀ ਵੱਡੀ ਬਹੁ-ਗਿਣਤੀ ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਵਿਚ ਹੈ। ਇਸ ਲਈ ਇਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਵਿਚ ਰਾਜਨੀਤਕ ਹਿਤਾਂ ਲਈ ਕੁਦਰਤੀ ਖਿੱਚ ਹੈ।

ਬਿਨ੍ਹਾਂ ਸ਼ੱਕ, ਭੂਤਕਾਲ ਵਿਚ ਦੋਵੇਂ ਇਕ ਦੂਜੇ ਤੋਂ ਦੂਰ ਗਏ ਹਨ ਅਤੇ ਦਲਿਤਾਂ ਕੋਲ ਖੱਬੇ ਪੱਖੀਆਂ ਦੀ ਬੇਧਿਆਨੀ ਦੀਆਂ ਕੌੜੀਆਂ ਯਾਦਾਂ ਵੀ ਹਨ ਪਰ ਪਿਛਲੀਆਂ ਨਿਰਾਸ਼ਤਾਵਾਂ ਦੇ ਹੁੰਦਿਆਂ ਵੀ ਅੱਜ ਦੇ ਮੌਜੁਦਾ ਦਲਿਤ-ਮਜ਼ਦੂਰ ਜਮਾਤ ਦੀ ਨੁਮਾਇੰਦਗੀ ਦੇ ਖਲਾਅ ਵਿਚ 'ਜੈ ਭੀਮ' ਅਤੇ 'ਲਾਲ ਸਲਾਮ' ਦੀ ਸਾਂਝੇਦਾਰੀ ਦਾ ਤਜ਼ੁਰਬਾ ਮੁੜ ਕਰਨ ਯੋਗ ਹੋਵੇਗਾ।

ਅਨੁਵਾਦਕ : ਪ੍ਰੋਫੈਸਰ ਜੈਪਾਲ ਸਿੰਘ (ਦੀ ਹਿੰਦੂ, 14 ਅਕਤੂਬਰ 2016 ਵਿਚੋਂ ਧੰਨਵਾਦ ਸਹਿਤ)

G. Sampath

On September 16, Parliament Street near Jantar Mantar witnessed a Dalit

rally that was unlike other such events in the recent past. What set it

apart was the number of speakers from the Left. Sharing the stage with

Prakash Ambedkar, Radhika Vemula and Jignesh Mewani were the likes of

Sitaram Yechury, Sudhakar Reddy and D. Raja. And surprisingly, for a

gathering that self-identified as ‘Dalit’, the rallying cries of “Jai

Bhim” were accompanied by a slogan rarely heard outside Left circles,

“Lal Salaam”.

Such an alliance of Jai Bhim and Lal Salaam, if translated into a

political programme, could mark a significant departure for both Left

and Dalit politics. The recent Dalit agitations in Gujarat offer a

glimpse of what may be possible if a fusion of Jai Bhim and Lal Salaam

were to go beyond sloganeering into the realm of praxis.

Lessons from Gujarat

The mobilisation in Gujarat

following the Una incident, in which Dalit youth were assaulted by cow

vigilantes, has already achieved two substantive victories. First, the

protesters successfully pressured the State administration to initiate

the process of distributing 220 bighas of government land to 115 landless Dalit families of Saroda village in Dholka taluka of Ahmedabad district.

The second success came from the 6,000 safai karamcharis (sanitation

workers) of the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC), who went on

strike for 36 days. Their demands included regularisation of contract

workers, provision of provident fund (PF) scheme and health benefits,

guaranteed minimum wage, safety equipment for all workers, job for kin

in case of accidental death or injury, and clearance of PF arrears from

2011. Every one of these is a material demand, and they were all

accepted by the AMC.

These are two instances where Dalit anger was channelled into pragmatic

political projects by identitarian outfits such as the Rashtriya Dalit

Adhikar Manch and Una Dalit Atyachar Ladat Samiti, as well as trade

unions such as Gujarat Federation of Trade Unions and Gujarat Mazdoor

Sabha, along with civil rights bodies such as Jan Sangharsh Manch. While

the beneficiaries of this mobilisation were Dalits, the demand-making

was premised not on identitarian but a material basis. Land ownership

and permanent employment with social benefits make a big difference to

the material existence of Dalits. But a militant articulation of

material demands has rarely been a consistent feature of Dalit politics.

This lacuna finds an inverse parallel in Left politics as well, which

has never seriously taken up caste issues — neither atrocities against

Dalits, nor casteism in general. It has restricted itself to class

politics without challenging the caste underpinnings of class

exploitation. A major reason, apparently, was the fear of dividing the

working class along caste lines.

But the Indian working classes were already split along multiple

identitarian axes, most prominently caste. The Left’s failure to counter

this caste-based division is one of the reasons for its marginalisation

in Indian politics. Ambedkarite critics blame the upper-caste

domination of Left leadership for its blindness to caste exploitation.

Indeed, there are few Dalits, if any, in the political bureaus or

central committees of the Left parties.

At the same time, the Left’s criticism of Ambedkarite identity politics

is not without substance. This critique was best expressed by Anuradha

Ghandy in an essay on the “caste question”, where she writes that “the

ruling classes have consciously sponsored an elite among the Dalits who

have consciously appealed to Dalit solidarity and a sectarian approach,

while denying any unity with other exploited sections and parties

representing them.”

Limitations of identitarianism

Ms. Ghandy’s fundamental point that Dalit-OBC unity is “practically

impossible to sustain” due to class contradictions has been borne out by

recent events. In different parts of the country, the dominant

agricultural castes have begun to mobilise — not against the upper

castes who own land or capital, but against Dalits. After the Gujjar

agitation in Rajasthan, Jats in Haryana, and Patels in Gujarat, Marathas

in Maharashtra have now taken to the streets demanding reservations.

Plus they have another demand: dilution of the Scheduled Castes and

Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act.

Not surprisingly, there is a creeping realisation among a section of

Dalits — most visibly in Gujarat, where they constitute a minuscule 7

per cent minority — that identity politics can only take them so far.

This realisation entails grappling with three painful truths about the

Indian political reality.

First, within the electoral system, identity politics can only yield

brokers of Dalit votes, who can, at best, extract minor concessions for

Dalits without challenging the caste order, and at worst, pass off

personal aggrandisement as empowerment of the community. Leaders like

Ramdas Athawale and Udit Raj exemplify this phenomenon. As for

Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), its political potential has been

curtailed by an extreme concentration of power in one individual — a

disease endemic to political parties in India.

Second, Dalit-OBC unity — a minimum requirement for identitarian Dalit

politics to gain critical mass — is a non-starter due to class

contradictions. A glance at the castes of the accused in atrocity cases

would be enough to put the idea to rest.

Finally, with public sector disinvestment and privatisation becoming

official government policy, reservations can no longer be the answer for

the vast majority of Dalits. This is a reality that other dominant

castes agitating for reservations are yet to come to grips with. But

they, too, will have to, sooner than later. If we think beyond

reservations, what else can identity politics promise, let alone

deliver?

Sheer political logic therefore dictates that Dalits look for allies who

share their social, political, and material predicament — in other

words, look beyond identity politics. For, on their own, they do not

have the numbers — either to retaliate in kind against their caste

oppressors or to avoid being reduced to vote banks for parties

controlled by their caste oppressors.

To take a recent example, the violence sparked by cow vigilantism

targeted both Muslims and Dalits. It even prompted calls for

Dalit-Muslim unity. But Muslims are a minority identity too. This

alliance is fraught with not just class but also caste contradictions

that could easily undermine it, as the failed attempts to forge

Dalit-Muslim unity in Uttar Pradesh show.

Dalit politics at the moment does not have an answer to class

collaboration between their own elites and their caste oppressors; nor

to caste collaboration between the poor and wealthy classes of their

caste oppressors. It cannot move forward unless it is willing to

articulate the material aspirations of the dispossessed — not only among

the Dalits, but also the OBCs and the upper castes. These would include

the landless, the contract workers, indebted farmers, and migrant

workers.

Similarly, Left politics has no future unless it serves the democratic

aspirations of the socially oppressed, and recognises that annihilation

of caste is the condition of possibility for any progressive politics.

In a semi-feudal, partially modernised nation like India,

anti-capitalism has little transformative potential without

anti-casteism. Such an understanding would entail the Left joining hands

with Dalit forces, and attacking casteism with the same kind of energy

it reserves for condemning imperialism.

Natural affinity of interests

A convergence of Left and Dalit politics is hardly new though. Marx and

Ambedkar have come together before, especially in the 1950s when

Ambedkar, together with the Communist Party of India, led struggles for

distribution of government land for landless Dalits. Then in the 1970s

came the Dalit Panther movement in Maharashtra. It took a combination of

state repression, upper caste violence (led by the Shiv Sena) and

co-option through prizes and electoral tickets to neutralise this wave

of militant left-wing Dalit assertion.

Today, a confederacy of casteist forces with control over capital and

the state apparatus are on one side, and a mass of socially oppressed

and economically marginalised are arrayed on the other. The ruling

elite, as ever, are conscious of their class interests cutting across

caste lines. But the working classes, especially the Dalits and OBCs

among them, stand divided into a great number of identities that are

locked in mutual antagonisms, designed to ensure that their identity as a

class remains buried.

The Dalits need the Left because there is no other political formation

that programmatically raises working class issues such as a living wage,

job security, pensions, and abolition of contract labour. As for the

Left, sheer survival requires it to raise Dalit issues. Given that the

overwhelming majority of Dalits are working class, there is a natural

affinity of political interests.

Of course, the two have fallen out in the past, and Dalits have bitter

memories of betrayal by the Left. Past disappointments notwithstanding,

in the current vacuum of political representation vis-à-vis

Dalit-working class interests, a partnership between Jai Bhim and Lal

Salaam may yet be an experiment worth revisiting.

Thanks to THE HINDU